Returning to the River: A Review of Peace Like a River

January 13, 2026 | blog, book reviews, news

Review by Ron Menchaca, MFA ’27

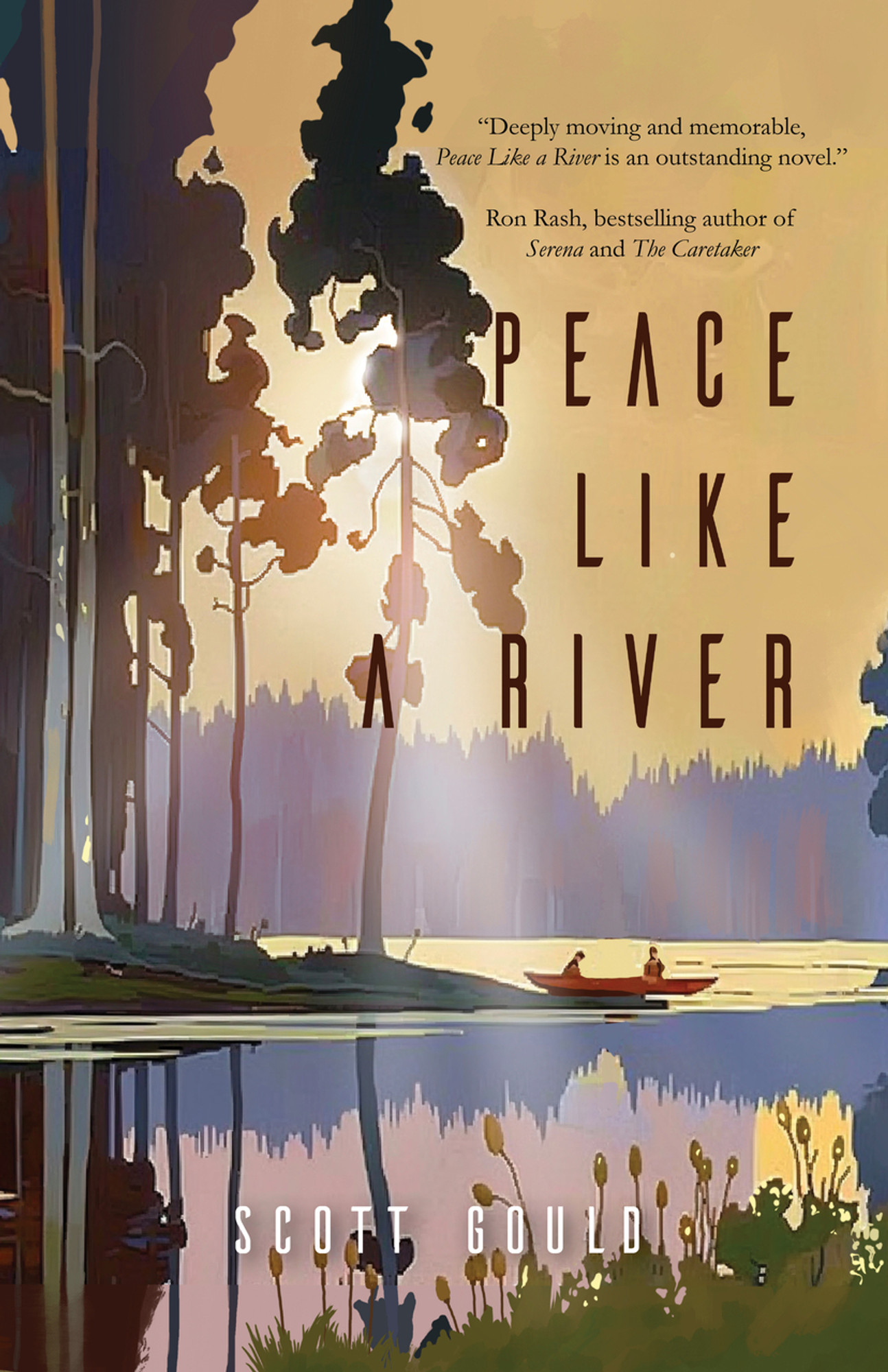

Peace Like a River

208 pp. Regal House Publishing. $19.95

Scott Gould knows every bank and bend of the Black River—its murky depths and dangerous shallows, its power to dredge up old wounds and mystical ability to heal them. The river is central to Gould’s latest novel, Peace Like a River (Regal, 2025), which follows sixty-something Elwin McClennon as he returns to his hometown of Kingstree to visit his dying father.

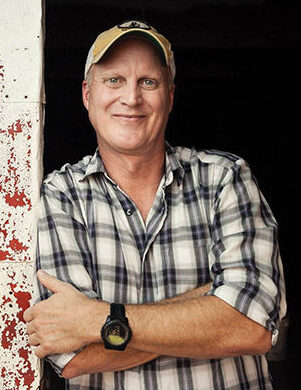

This is Gould’s sixth book. His third novel, Things That Crash, Things That Fly, won the Eric Hoffer Award for Fiction, and his fourth book, The Hammerhead Chronicles, won a 2022 Memoir Prize for Books. Often inspired by real events, people, and places, Gould is fond of telling his creative writing students at the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts & Humanities to write what they know—as long as they know it well enough to lie.

Set in the South Carolina Lowcountry in the present day, the novel explores the complexities of father-son relationships, place, memory, and repressed childhood trauma. For Elwin, the trip back home tears open an unhealed psychological wound and forces the protagonist to reckon with his painful past.

Gould’s adeptness at describing his sleepy hometown through the eyes of his main character has a universal quality that makes his writing relatable to anyone who has ever returned to a formative place after a long absence. Transporting readers back to his 1970s childhood, the author revisits the peculiarities, contradictions, and eccentric characters of the small-town he fled fifteen years earlier.

The plot gets moving when Elwin receives a call from an old neighbor who has become his father’s companion in the years since Elwin’s mother died. The Old Man, as Elwin refers to his estranged father, is sick and dying. He hasn’t seen his father since he left, and their reunion forces Elwin to confront a long-kept secret about the death of his childhood best friend Lonnie Tisdale, a name that readers of Gould’s debut short story collection, Strangers to Temptation, will recognize.

Riding shotgun on the trip is Elwin’s son Thom, a mildly autistic teenager with a caustic wit who shuts out the world, especially his father’s oft-repeated stories, with ever-present earbuds. Thom is thirteen, highly regimented, and whip-smart, while Elwin is unorganized and spontaneous. But the surprise trip throws both father and son off-kilter.

Elwin is muti-layered and believable as a gloomy, self-deprecating, department store worker. He shares custody of Thom with Roma, a much younger woman with whom he had a one-night stand and never married. Roma has vacation plans and can’t watch Thom, so Elwin takes the boy along to Kingstree to meet his dying grandfather for the first time. The supporting cast is a motley assemblage of well-developed characters—from a pot-smoking motel owner and his precocious bookworm daughter to a funeral home director who moonlights as a real estate agent and a stray cat named Willie Nelson.

Upon returning to the river that largely defined his childhood, Elwin is consumed by gut-wrenching memories of his father’s frequent absences and tough-love parenting. It doesn’t take long before Elwin and his father, a disabled Vietnam veteran, fall back into old routines. The father berates his son for feeling sorry for himself about things that have gone wrong in his life. “The world don’t owe you jack shit,” the Old Man says. “Question is, what are you gonna tell that boy of yours about the world?”

Elwin struggles to establish a meaningful connection with his son. But after a series of events shakes them both from their self-centeredness, they begin to see each other differently. At times, Thom seems too wise and worldly for his age. Yet his blunt observations about life and family are among the story’s funniest and most endearing parts. Within minutes of meeting his grandfather, Thom asks, “What is killing you?”

While Elwin’s childhood and current life are explored, the fifteen-year gap between his departure from and return to Kingstree leaves a sizable hole in the story. We don’t get much information about his relationships with Roma and Thom during this period. It’s as if Elwin exists only within the context of his hometown, leaving readers to wonder how he lived in the intervening years. This missing period could easily be a new chapter, which would not only provide a smoother transition between the 1970s and the present day but would also address obvious questions about what it was like for him to help raise a child on the spectrum and how he felt about his own father in the years after he moved away.

Because many of the key scenes take place around the Old Man’s riverside fishing shack, the river and its indiscriminate power to claim whatever it wants drive the narrative. At times humorous, tender, and terrifying, the novel mirrors the unpredictability of the river itself: sometimes rising and rushing violently, other times placid and peaceful.

All three generations of McClennons undergo transformation over the course of the novel. The Old Man shows a softer side with his grandson; Elwin confronts his childhood trauma; and Thom, after losing his phone and unable to use his earbuds as a social barrier, becomes smitten with the motel owner’s daughter.

After the Old Man passes, the entire cast gets involved in carrying out his final wishes regarding the spreading of his ashes, which puts Elwin back on the same river that claimed Lonnie Tisdale decades earlier. Returning to the bridge where Lonnie jumped into the shallow river, Elwin must come to grips with what he knows but has never shared about his friend’s death. He begins to reevaluate his feelings about his deceased father and his strained relationship with his own son.

Beautifully written and deeply moving, Gould’s novel flows like a river, tracing the origins of pain, the passage of time, and the winding path to forgiveness.

Scott Gould is author of six books, including The Hammerhead Chronicles, winner of the Eric Hoffer Award for Fiction, and Things That Crash, Things That Fly, which won a 2022 Memoir Prize for Books. His other honors include a Next Generation Indie Book Award, an IPPY Award for Fiction, the Larry Brown Short Story Award, and the S.C. Arts Commission Artist Fellowship in Prose. His work has appeared in a number of publications, including Kenyon Review, Black Warrior Review, Pangyrus, Crazyhorse, Pithead Chapel, Garden & Gun, and New Stories from the South, among others. He lives in Sans Souci, South Carolina and teaches at the S.C. Governor’s School for the Arts & Humanities.