Mapping One’s Creation: Review of Bruce Snider’s “Fruit”

June 3, 2020 | blog, book reviews, news

By Joshua Garcia

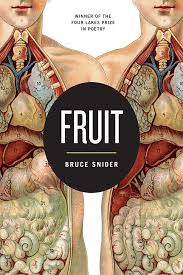

Fruit

By Bruce Snider

96 pp. Wisconsin Poetry Series. $16.95

Nearly a decade since Paradise, Indiana reflected on youth like a fever dream of home, grief, and first love, Bruce Snider’s third collection, Fruit, remains mindful of the past yet looks unflinchingly forward. The title, ripe as it is with suggestion—offspring, the temptation to original sin, an epithet for a gay man—hovers over Snider’s new work. Snider’s poems are unafraid to examine origin stories and excavate what is passed down to us, whether gender, belief systems, or genetics. Fruit asks the questions, What next? What do we create with what we’ve inherited?

Readers will find more of Snider’s Indiana in Fruit, with its share of schoolyard bullies, livestock, kissing at the 4-H fair, ruminations on father’s cologne, and a crocheting Aunt Bev. Snider’s new obsessions, however, include storks, conception, genetics, and childlessness. A gay man’s fixation on procreation reverberates throughout the collection in recurring prose poems sharing the title “Childless”: “All morning, the poplars rattle, repeating green. They hoard their sticky pollen, then release.” As much as Snider invites us into the deeply personal, his poems often stand apart from their subject matter as outsider, voyeur. Whether navigating a coed baby shower, passing through museums, or reading Wikipedia entries on homosexual behavior in moths, Snider’s voice is one that has been othered, if not by nature, by what we’ve extracted from it and woven into a collective creation mythology.

Snider reflects on his own creation both literally, ruminating on the first six weeks of his development, and figuratively as the descendant of a sheep-farmer: “I’m born to thunder / in the veins, a child of form, a rusted gasket ring, some / disenchanted thing, the promise of a worm.” As Snider explores what is passed down through nature and nurture, there is an underlying tug of war between masculine and feminine. The same voice that cleaned his father’s guns observes the father-son relationship of neighbors, “Even I doubt how a man can mother / when I see the neighbor shout, chuck a stone / at his son.” Caught in the chain of inheritance, linked like his own sonnet crowns, Snider questions in “One Day, He Said, I’d Carry on the Family Name” what of his person is his own, striking at feeling with a clever, biting rhyme:

What in me, I wonder, is me

as the world goes on copying itself—

black seeds sprouting green,

egg sacks on the gray spider.

I walk to where iron gates open

to the corner graveyard and

the stones say: Snider, Snider, Snider.

Some of the most touching and powerful moments in Fruit come when Snider writes of life shared with a partner. In one “Childless” poem, Snider writes, “Later, in our rental car outside the city, we hold hands, passing acres of trellised vines, grapes ripening along the highway, arguing for wine.” The components for life-making are there: When two people love each other very much. . . . But what does that look like if those two people are both men? In a poem about the father of genetics, Gregor Mendel, Snider asks, “What, at this late hour, can he leave / behind?”

Master that Snider is at composing the lyric ordinary, Fruit infuses the plain, messy, joyful, and sad with viability. Snider’s poems are familiar with grief, but there is a generative energy folded into his words. Following a map encoded in the body, Fruit invites the reader into a love story which may or may not result in procreation but, nonetheless, takes the hand of life itself.