Fragmentation, Apocalypse and the Anti-Novel: An Interview with Dan Leach

November 11, 2025 | blog, Interviews, news

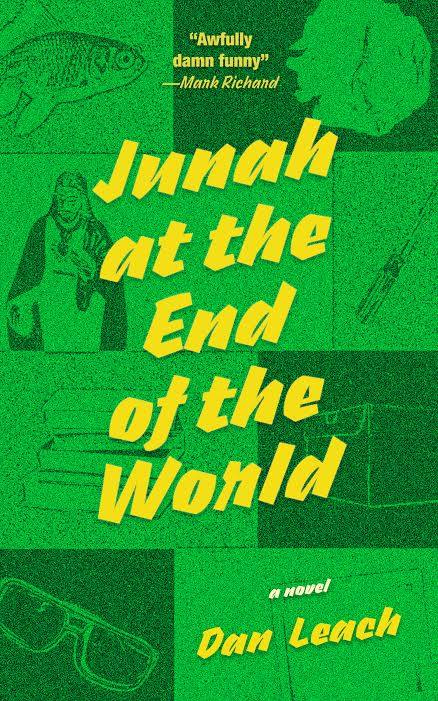

As someone who was in middle school during Y2K and 9/11, I (James Passaro, MFA ‘26) understood the times and seasons of Junah at the End of the World. Dan Leach’s portrayal of a middle school boy in Carolina who is navigating his parent’s separation, his first romance and the looming threat of apocalypse is a journey into a literary shoebox time capsule. The novel, or anti-novel, provokes curiosity and empathy as it explores what to make of the work one does and the relationships one has as they navigate endings. It was my joy and privilege to talk with my friend Dan Leach about his 2024 South Carolina Novel Series award-winning novel Junah at the End of the World.

Junah at the End of the World

224 pp. Hub City Press. $17.95

How does the use of fragmentation play into the description of your novel as an anti-novel?

Regarding the anti-novel, I would recommend a book called Reality Hunger by David Shields. Shields argues that in the Victorian era, when the privileged housewife cracked open Jane Eyre, she was hungry for a certain kind of reality that a 500 page linear plot provided. He argues that our minds don’t really work like that anymore. Because of the smart phone and the speed in which we process information, we’re probably more attuned to the fragment than we are to a novel that is a slow burn, with gradually rising plot and well-developed characters.

Novels deliver a sense of development in characters, dramatic action, and normally feel very connected. When I set out to write Junah at the End of the World, I intended to do all of that. I wrote in 2020 during COVID when everything was shut down, holed up in a little garage writing scraps with the voice of a precocious twelve-year-old kid who says some wild things, about the south, about faith, and about this looming event known as Y2K. I didn’t arrange them as one would a novel. I let that voice speak. Sometimes it came out as a proverb or aphorism or resembled a vignette. But there was no arc.

Fiction writers typically think in terms of the stakes, tension, and conflict. I didn’t think about any of that. I told myself that after I wrote those fragments, I would go back and add the connective tissue and shoehorn things where they needed to be. I realized that I was writing a novel that read like a mixtape, a little essay, or a fragmented anti-novel. I let it be that and was happy how it turned out, and I think it fits the message of the book.

When you started writing these fragments were you thinking about a reader’s attention span?

The truth is, I’m always thinking about my own attention span. Everything we write has to go through the filter of: do I find this funny or do I find this interesting or where am I getting bored? With that being said, I’m probably undiagnosed with ADHD. My mind jumps. I’m not a long, intense fixation kind of guy. I hop from topic to topic, so that was informing the way the book is structured, which is to say, in short bursts, clips, or riffs. The jumping is often based on associations rather than dramatic action.

I was also thinking about my own kids and the degree to which they interrupt my writing. I have four young kids. They’re sweet but totally unsocialized. We home school, so they burst through a door with whatever feels pertinent to them. They tell me about playing Nintendo Switch, or mastering a chess move, or wanting to show off their choreography. I started to write in short bursts knowing that at any minute the garage door could kick open, and I would have something to attend to. Had I written this when I was twenty-three and unmarried with ten hour stretches to ponder, I could see things being a little bit longer and more loose in how it would unfold.

How has childhood and fatherhood informed your writing in the last few years?

I envy writers who get really interested in a concept or a political issue. They find something at work in culture and write in response to that. I’ve never been that way. I always write directly out of life which is part of the influence of David Shields. For him, everything is a collage of both literary artifice and lived life. How one patches all that together answers the question of what art is to you.

For me, I’m a dad. I teach three days at a college and the other four days, I’m very non-professorial. I am invested in making grilled cheese sandwiches, supervising Wiffle Ball games, delivering homeschool lessons, and playing Zelda. It’s incredibly non-academic and in some ways non-creative, yet in a lot of ways very creative. When I finally get a free minute to sit down and write a short poem or a novel, I’m thinking of childhood, parents and kids in this weird historical moment, in which I happen to be raising kids.

It’s very different from the world in this novel. I wrote it as I was processing COVID, which felt like an apocalypse that may or may not come, and remembering the Y2K that I lived through as a teenager. I realized that my kids will never know the world that I grew up in, a world without smart phones or the presidential candidates such as we have now. Mine was a cleaner world, a world of cul de sacs and abandoned grocery stores, take one leave one libraries, and fields, and dried up drainage pipes. It’s the world of the ’90s and readers who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s find the book nostalgic, with a very familiar landscape. I dedicated the book to my kids because I wanted them to have some kind of access to the world that I grew up in.

Can you speak to how fragmentation and how apocalypse as a genre might be connected?

I could speak about it theoretically and then speak about it practically. In the novel, Junah is given an assignment to make a time capsule. When he walks into his sixth grade classroom for the first day of school on the chalkboard the message is written, “The end of the world is here.” It’s this announcement of the apocalypse. Junah’s assignment is to fill a shoebox with what it means to be alive in Carolina at the end of the world. When you think about what a time capsule is, it is by definition fragmented. It’s disparate, yet related items placed in a curated space. In his box, he puts in a Swiss Army knife, a plastic dashboard Jesus, his sunglasses, a Polaroid, the note that he wrote his first crush, and transcribed stories about the adults in his life.

He puts these in and is very self-conscious. He announces to the reader that you may not know how all of these things are connected, but I do, and I’m placing them in here. Their inclusion tells you that they are important, but you’re gonna have to tell me exactly what some of these connections are. As a kid in the ’90s, you might have made a time capsule. Now, I think we post on Instagram. Those are curations of the best memories, the best pictures, the hottest takes, of places we go, and the people we love. I think those are the new time capsules. They happen to be digital and the walls are a bit wider, and we fill them with more, but I think we’re doing the same work of trying to save what matters.

Theoretically, the connection between apocalypse and fragmentation is that apocalypse concerns us. It threatens death and calls into question what it means to live. For a certain kind of person, that throws your mind all over the place. I think about COVID during those early hysterical months. I wouldn’t have described myself as a focused person. Like a lot of folks, I wasted hours in doomscrolling, flicking from the murder of George Floyd, to the January 6 insurrection, to a cat playing piano. It’s high and low, comedy and tragedy, and when you move through this variety of content, tones, and philosophies, I think it does fragment you. I don’t know that peacetime necessarily means that you start thinking in the long form, but there is something about the apocalypse that philosophically throws you.

For Junah, his mind is being thrown too. That shoebox became a kind of mercy, a place where he could collect thoughts and had a sense of agency even if the larger world felt out of control. In that way, the book played the same role in my life that the shoebox did in Junah’s. It gave me work to do, when I was being told by my employer that I may not be offered another year on my contract or when I was told by friends that the vaccine I took might corrupt my DNA and explode my heart or when I was told by the larger political world that we’d never go back to normal. There were all these forms of chaos, but I knew that if I showed up in the garage, there would be this book and this 12 year-old kid waiting for me to write. I think it might be read as a book about the work you do to keep your sanity when everything around you feels apocalyptic.

That reminds me of a scene where Junah is reading in a self-checkout library to escape or rebel from thinking about the end of the world. Is reading itself consistently a rebellion in the face of the world ending?

I would’ve said in 2020 that reading is an act of rebellion. I would say it all the more now in 2025. We’re three years in this experiment with AI, and I teach lower level composition classes and upper level workshops to a group of students for whom it is now normal to ask chatGPT to summarize a book that they were assigned or to ask Google Gemini to give the main points of a book which may be difficult or long or arduous. Reading has become all the more an act of slowing down, in a world moving fast, competing for your attention, in a world that has numerous sources or companies not to sound too conspiratorial, that want to direct your attention. You also direct your attention when you move through sentences, paragraphs and linger over words, learning empathy while reading. It may have been George Eliot that said we come to literature to have our empathy renewed. I have found that to be true. I have found access to different perspectives, more generous and complex language, and more honest language for what I feel other people feel.

I don’t know if the larger world is interested in that. I think that the larger world wants us numb, sedated, and ready to click by. A very common designation for my students is that they were an iPad baby or their parents put them in front of a screen. They’re the first generation of digital natives for whom reading feels like a rebellion, if only because it’s harder work.

In the novel, Sadie is Junah’s first romantic interest. She moves and it’s sudden for him when she does. It reminded me of another short story of yours from your collection Dead Mediums. The story “Fixers,” features a female character named Juna who disappears from the life of the main character in a surreal way. They both send postcards. Was there a connection for you with these two stories?

100% and I love that you found that connection. It’s going to sound like I’m making a PSA for the anti-novel right now, and in some ways I am. One of the things I realized in writing a book that functions like a collage is that you can take past material and embed it. This novel is only about 40,000 words. I think Hub City Press added white space and helped out with the margins to get this thing sitting between covers and with a spine of appropriate width, but it’s a very short book. It allowed me to take things that have appeared in past books.

In “Fixers,” a marriage falls apart and a husband gets letters from his wife, oftentimes that don’t feature anything more than a blank postcard. It’s an invitation to interpretation, an invitation in the case of “Fixers” for this husband to imagine where she is and what she’s doing. It’s just enough to say, “I’m still alive” but not enough to give you any sense of closure or direction in terms of where she is. I wanted to use that mechanism. In Junah, Sadie reaches out from Florida with a series of really strange and in their own way loving but also frustrating postcards.

There’s probably upwards of fifty things slightly repackaged or reconfigured that I fit into Junah. Again, reading David Shields, I’m thinking about how a work of collage can let some of those threads show for a reader who is careful to pull on the thread. Suddenly you realize, this is from an essay, or a poem, or another work of short fiction. I like the way it sets other elements down in the same shoebox so to speak.

To bring this to a close, are there any questions you have for the reader of Junah at the End of the World?

Something I say frequently to my students is you’re the only one who can’t read your work. The thing that exists in your head, as a fixation and eventually becomes contained in language, you can see how it is received by a reviewer or a beta reader or a good friend, but you can never really tell what it is like to be on the other end. So I think my only question for any reader has ever been: what in here sings? What in here will you remember? You could read this book in two hours, maybe less if you read quickly. I would love to know what lives on, what images still feel vivid when you think about it, what sentences still seem interesting, what themes and concepts have been useful as you process your own apocalypses. And if I could give a final one, I’d love to know what people think happened on the morning of January 1. When he wakes up tomorrow, who is Junah? What world does he occupy? Is it the old normal or a new normal? If so, what makes it new? I think ending on a note of ambiguity makes me curious to hear what readers think happens when he wakes up and the world both is and isn’t still there.

Dan Leach has published poems and short stories in The Massachusetts Review, The Southern Review, and The Sun. He is the 2023 recipient of Texas Review Press’s Southern Poetry Breakthrough Award, and his collection Stray Latitudes was released in 2024. Junah at the End of the World, his debut novel, won the South Carolina Novel Prize and was released by Hub City in June 2025. He lives in the lowcountry of South Carolina and teaches poetry at Charleston Southern University.