First Kiss

Kathleen Blackburn | Essays

When I was thirteen, and still trusting that Lubbock, Texas could be the whole of the world, I kissed a boy from church named Adam. Our church upheld God’s word as literal, but that’s not why the kiss came to be my first sin. Adam was sixteen, the son of a cotton farmer, and for a while in the late nineties, he spent Sunday afternoons with us.

I use the word “us” deliberately here. My mom didn’t allow me to be alone with Adam. He drove a rusting blue 1986 Nissan Z-280, which only had two seats, so I never rode with him. The 10:30 a.m. service at Grace Church would commence, and Larry Doyle, a graying willow of a white man would hold vertical his palm before his head and sermon that every tree did clap its hands in praise, though there be drought. Larry was no trained preacher, but had been called from his prior work as an electrician. He would pray over my dad, who withered with cancer when I was twelve. At my dad’s funeral, Larry read from Psalms, and the small congregate of Grace Church brought casseroles after. The church building claimed a corner of 34th Street, one of the oldest streets in Lubbock. Twenty years now, but I remember the white double doors that opened to the brash noon light and the view of Adult Books, the city’s only porn shop. Adam, a scrappy white boy with the eyes of a husky, would walk down the parking lot, then follow the family van as my mom drove home.

Adam and I watched movies with my family, played card games with my family, and walked the dogs with my family. Each activity was accompanied by at least one of my younger siblings and usually all four them, trailing in an unfurled line of wonder that I had acne and a crush. Always, there was my mom. That Adam and I kissed was a miracle of timing and temporary reprieve from her rigidity. I was homeschooled, and she expected me at the kitchen table, which doubled as the school table, promptly and fully dressed by 7:30 a.m. I had friends I’d met at church, but our phone conversations were to occur between 3:00-7:00 while I sat at the kitchen table, and not to exceed twenty minutes. My mom typed a set of ten house rules so as to mirror the Ten Commandments and hung them on the refrigerator. They were essentially the originals from Deuteronomy, but “Thou shalt not murder” was replaced with something about refraining from fighting with one’s siblings, and “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” which was too raunchy for my mom, supplanted with “Take care of what God gives you.” There was also an essential reordering. My mom moved “Honor thy father and mother” from fifth to second commandment, right below monogamy with God. Before breakfast, but after I completed a math lesson, she asked me to recite the house rules as she scrambled eggs. As I look back now, I am struck not by her standards, but by the ferocity of the consequences when I failed them. She was not only exacting, grounding one of her children over a poorly wiped counter or a forgotten trash bin, but unpredictable. I could rarely call the score of a spat with my sister or a too-long phone conversation. Punishment was not measured by the action, but in the depth of the offense, all of which she seemed to take personally. For all the time spent in morning rehearsals of the house commandments, there might as well have been one. “Honor thy father and thy mother,” and with my dad gone, and gone early at the age of 39, there was only my mom. It wasn’t easy for either one of us.

The afternoon in question was to be like every other Sunday afternoon. We had a lunch of cheese sandwiches on homemade bread, and Adam and I were lounging in the kitchen, talking awkwardly. I was forever laughing and rubbing my face in place of knowing what to do or say.

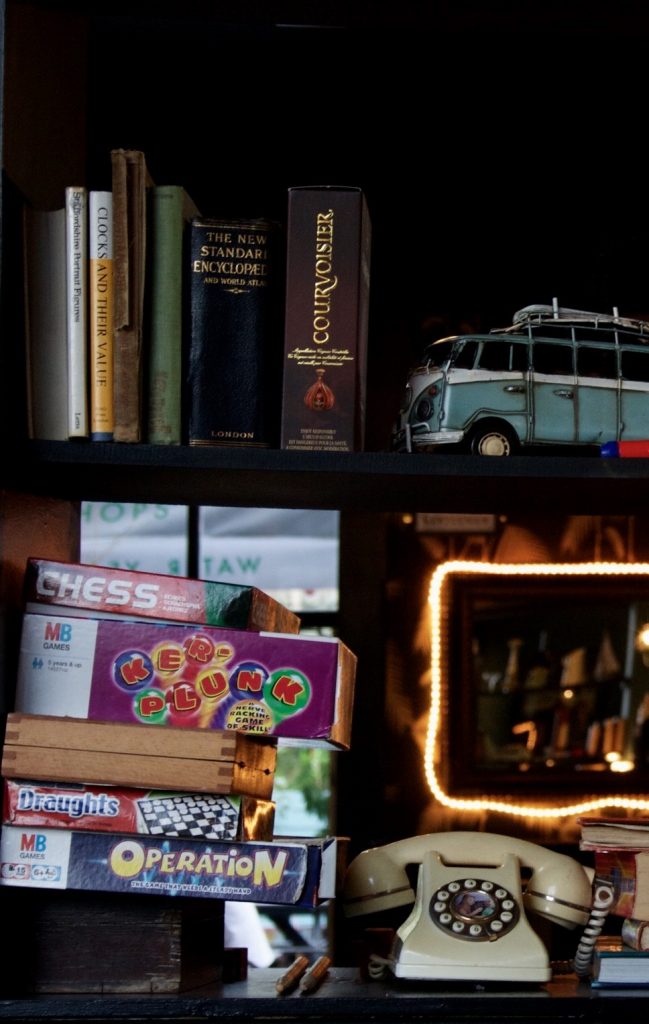

“Stop touching your face, Kate,” my mom said. “It’s bad for your skin.” She then suggested that we play a board game. “Why don’t you and Adam pick one out?” she said, leaving me almost speechless with joy. The games were stacked on the shelves of my younger brother’s closet. His room was in the back of the house. Adam took down the game Yahtzee. He turned to face me and leaned in slowly. I had my first kiss over an orange Yahtzee box in my brother’s closet.

Along with conventional medicine, public education, and rock ‘n’ roll, my mom had flatly rejected the notion of dating. Dating, with its exclusive one-on-one time, was for the promiscuous. Those who practiced it were more interested in carnality than the actual person. Indeed, because of dating, young men and women were blinded to each other’s true character by their physical attraction to one another, confusing their sex drives for love. This led them to disastrous marriages that ended in the larger disaster of divorce, worldly relationships, and, worst of all, the premarital loss of virginity.

My mom’s dating beliefs (which she developed as a mother; she dated in her prime) were largely influenced by an evangelical speaker named Greg Harris, a Focus on the Family celebrity with eight kids. He spoke on, among other things, the merits of homeschooling, corporal punishment, and how to keep your kids abstinent. His eldest son, Joshua Harris, went on to write I Kissed Dating Goodbye, the seminal text on twenty-first century courtship between virgins. I can still see the cover of that book: a moody blue photograph of a young man in a suit, tipping his fedora in farewell, presumably, to dating.

The thesis of the book is in its title, and Harris argues that the only way to really get to know someone is in the context of her entire family. One cannot hide, Harris contends, her real self around family. It is within the familial context—the dinner table, the board games, the lake house vacations—that the essence of a person is revealed. This is important because the entire purpose of getting to know someone of the opposite sex is to determine whether or not you would make suitable, lifelong, monogamous mates for one another. Sex cannot be factored into the equation. Rather, sex is the reward for the restraint required to fully learn a person. As a result, sex is not the expression of self, but the goal of identifying a worthy partner.

I Kissed Dating Goodbye broke out of the homeschool fringe, though Greg Harris homeschooled his children, including Josh. The book enjoyed wide readership among evangelicals, bolstering, as it did, the platform of purity every evangelical woman was placed upon, and tempering the red-faced charged-dick drive of young Christian men. I remember the high school girls in my youth group reading it as a kind of Christian girl book club, and one of them exclaiming, “I’m not even going to kiss my husband until the wedding night.” I remember that Josh Harris said purity was not a line one tiptoed up to, brushing with her feet the boundary of the world so as to smell the musky-sweat-barnyard sex on the other side. Purity meant, and I quote from memory though I’d bet my life it’s accurate, running as fast as you could in the opposite direction.

My mom was way ahead of the I Kissed Dating Goodbye craze. Even while my dad was alive, she began to formulate her ideas about the romantic futures of her daughters. She and my dad went to hear Greg Harris speak and returned from the event to announce that we would court, not date, the opposite sex, beginning at the age of eighteen.

“What’s courting?” I asked my dad once. I remember that he and my mom were painting the living room hunter green.

“It’s when you meet someone and you feel attracted to them,” he said, rolling the paint on the wall and, I now think, avoiding eye contact with me. I was eleven or twelve, and puberty had made a miserable early arrival. My breasts ached. My sweat glands and pores leaked in a constant and mortifying announcement that my body would not be contained. I am sure my dad, who would be gone by the time I was thirteen, felt at a loss. “Maybe you go out dancing or for dinner or ice cream,” he said. “If you get along, maybe you say something like, ‘I’d like to see you again sometime.’”

“John,” my mom interrupted. “That’s dating.”

“Oh.”

My mom went on to explain that courtship meant you did not spend time alone together. You hang out in groups, large ones. The next step is to spend time with one another’s families. If that goes well, you spend time alone together, but only in public places, like coffee shops and church.

“Because in private,” she said, “there is too much temptation.” I think of that phrase now, too much temptation, and I imagine an eruption of sexual desire. The phrase suggests a game of seek-and-hide, something you would play with your partner to arouse each other to a point of crazy, clothes-tearing fucking. But my mom had a way of transforming the titillating into the terrifying. As children, we were not permitted to use any euphemisms for our genitals. My mom demanded anatomical precision. “It is not a veevee,” she said. “It is not a hoohah or a jay-jay, or a hmm-hmm, and it is not a belly button. It is a vagina. That is what you need to call it.” My mom’s seriousness and rebuke curled around her clear pronunciation of each syllable of “vagina” such that I almost apologized for having one. My sister Kristen ran from the room with her hands covering her ears.

My mom described courtship with equal precision, alluding to dining room scenes that could rival those in the A&E production of Pride and Prejudice. When I began courting at the age of eighteen, we would sit on the living room couch and visit with my family. We would play Phase 10. We would get to know each other through conversation involving everyone in the immediate bloodline, and we would determine, as a family, whether the union would meet the standard for the more perfect and holy.

It’s worth wondering, then, how it came to be that I was only thirteen when Adam began calling on Sunday afternoons. He plowed cotton fields for his father, and he was a high cheek-boned misanthrope who loved kung fu and the movie Fight Club. As I look back on it now, I can hardly think of a good reason to trust him. He had a weight bench and crossbow in his bedroom. He was suspicious of government and church leaders; he was also homeschooled and had dreams of significance. “I feel like I have a great purpose,” he once said. “I know I’m not just going to live a quiet life.”

No, it wasn’t because my mom trusted Adam, though he said “Yes, ma’am,” and made her laugh. My mom let me disappear for a minute because she had become certain of the grip of her authority. I am sure my mom believed that Adam would not dismiss her rule, that his deference for her would override his horny impulses. Her suggestion that we go choose a board game alone was not a lapse in judgment; it was confirmation, in her mind, of her absolute domination.

But it was for me a slip into the sweet air, and I felt the line from which I was supposed to run. It tasted like salt. It was a warm tongue. Adam kissed me over the Yahtzee box and then we walked out of the bedroom. I felt heat and water between my legs; I felt like I would never be the same. One of the many problems with the alt-dating approach is that it makes one far too prone to looking immediately for love, to romanticizing the very notion of a partner to the point of delusion. I had replaced the so-called blindness of physical attraction with the total blindness caused by treating everyone as a potential life partner.

I thought I was in love with Adam Sherrod.

By that evening, my flush had given way to something like a rock that pit-stomach ached at the center of me. I felt my first and secret kiss was lodged inside me like a splinter infesting, a shame that could only be removed, I told myself, through the plucking of my mother’s absolution.

Two or three days after the kiss, I woke up early. My sisters were still asleep and I knew my mom would be riding her black stationary bike. When my dad was still alive but dying of cancer, my mom rode the bike with her arms held up above her head. As though in worship, as if waiting to ascend. She said she was following Abraham’s example. While watching his tribe fight the pagans, Abraham was told by God that he need only hold his arms in the air to win the battle.

But the morning of my confession, my mom was bent over her Bible as she pedaled, one hand on the handlebar, the other cradling the book. The living room was lit by a single torch lamp by which she read. She looked up when I walked in.

“Can I talk to you?” I said.

“Sure.” She whopped closed her Bible and held it to her chest and pedaled. My throat dried up. I climbed into the green La-Z-Boy recliner, a twin replacement to the one my dad spent his final months in. I can still feel the soft short fibers of that chair, their lack of comfort.

“I kissed Adam on Sunday.”

There may have been more to this than what I remember. Knowing myself, I probably prevaricated for quite a while, um-ing and pushing strands of hair behind my ear again and again. But in my memory, I said only, “I kissed Adam on Sunday,” and my mom stopped pedaling. She swung one leg over the seat and stood. Then without a word, she walked out of the living room.

My mom did not speak to me for two days but for instruction to set the table or help clean the bedroom. She told my sisters that I had kissed Adam and they did their best to follow my mom’s example, ignoring my presence, turning away when I spoke. I remind myself that I was thirteen, Kristen eleven, Kelsey eight. The younger two were too young for this to be a memory. I remember speaking through the dark of our bedroom to Kristen, who slept on the top bunk above me. There was no response.

I don’t blame my sisters. I imagine their fear of our mom’s rebuke outweighed any amount of conscience or reason or affection. And they weren’t very good at shunning me anyway, forgetting and asking me to play in the backyard or to wear one of my shirts. But my mom was unrelenting. She called Adam on the phone and, in a voice I’m sure was as calm and sterile as a surgeon with a scalpel, told him not to do it again. Later, I cried to Adam in remorse in the Sunday school classroom at church.

“It’s okay,” he said. “But next time you decide to tell your mom anything, could you please tell me first?”

In the coming years, I explored what I could of sex despite the disaster of mom’s silence. My sisters, too, told me that when they saw what happened after I kissed Adam, they swore to themselves never to confess anything to our mom. They promised themselves this even as they participated in my punishment. What sense am I to make of this? Of course there are things to say about how we all experience our childhoods as normal until we don’t. As I think of my younger sisters as adults now, telling me that they learned not to confess, my mind returns to that list of commandments on the fridge. How I didn’t know the difference between obeying and surviving that second rule, my mother’s law. But I’m still not sure what I would tell that thirteen-year-old girl, that thirty-nine-year-old mother. There’s a better way, but what is it?

Adam was my pre-courtship boyfriend for two more years. We’d cover our laps with the couch throw pillows, watch a Harrison Ford movie, and unzip one another’s flies. After nearly a year, my mom started to let us retrieve

board games again. I learned how to give a hand job with Adam, and he slid his hand down my pants to make me orgasm. The first time I came, I grabbed his wrist. “It’s okay,” he said. “That’s supposed to happen.” We broke up unremarkably when he was eighteen and I was fifteen.

When Adam went to college he declared a history major so as to situate himself among it. Before he flunked out, he’d switched to engineering and then to pre-med. Whispers tracked down the homeschool line that he was drinking and smoking dope. Someone said Adam ran around with a big weed dealer in Lubbock County, another homeschooler named Mark Sunderman. Homeschoolers in Lubbock tended to come from white families with a vivid conviction about what it meant to be independent. We wanted a line with God as direct as the yellow lightning on the horizon. He would be the one to bring the rain, not the government. The last I heard about Adam was that he was working full-time for his father, farming cotton on land they rented, and that he was a drunk. The last time I saw him, I was twenty-four, and he was smoking a cigarette in the corner of a bar. When I looked again, he was gone.

Of course, the break-up happened in my living room. After Adam left, I turned to my mom, who’d been standing in the foyer long enough to know what had transpired, if not to witness the entire thing. “He’s walked out of my life forever,” I said. She put her arms around my shoulders and held me to her.

On the rare occasions when I’ve talked about my first kiss, I’ve said my mom’s silence lasted three days rather than two, as I’ve written here. In my memory, three days is accurate, but it’s hard for me to believe a mother would do that to her thirteen-year-old daughter, even if it was my mother and it was me. And then there’s the fallacy of memory: perhaps it lasted only a day. Does it matter? The truth is, her reproach has lasted twenty years. My mom’s fiercest form of disapproval has continued to be her silence. When I, at the age of twenty-six, broke off an engagement to a man she really liked but with whom I’d fallen out of love, she stopped speaking to me. When she discovered I was taking anti-seizure meds for my bipolarism at the age of twenty-eight, she said I was sicker than I had ever been and stopped speaking to me.

Perhaps I should slow down here; there are so many details. My fiancé and I were living twelve-hundred miles apart, and he had asked that I not call when I was lonely. His voice always had an exclamation point in it. And then there’s the part about how my meds gave me dry mouth and took my appetite away. I started eating cucumbers and looking at bright imaged paths of brain synapses because my short-term memory had turned to sludge. I wondered if the static in my brain had dimmed and if the reason for my relief was that I couldn’t remember anything.

The particulars change, but the story is always the same. One sign after another on an irredeemable chain. In my dad’s absence is my mom’s presence, commanding and unshakable in its certainty. Though my mom has recently said to me that she tried to be a good mom. “I thought I was,” she said. She is present when she’s not. Even now, I imagine her as I tell this, and I weaken. Shame, for me, feels like my mom walking away. Each rebuke reverberates back to that early morning.

And how would she tell this story? Perhaps she too would want to erase all the words, except for maybe sorry. Except for forgive me.