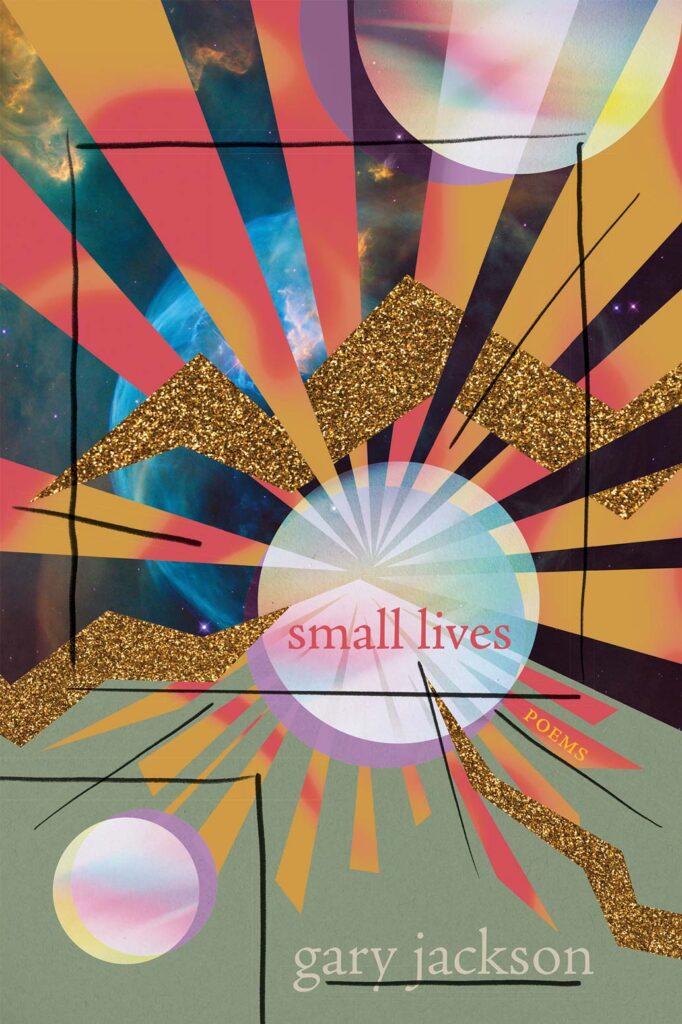

An Interview with Gary Jackson, author of small lives

Growing up, I (Mary McCall, MFA ‘26), was an avid comic book enthusiast and poet. So, I was extremely intrigued by Gary Jackson’s small lives and how his work intersects these two worlds. This poetry collection reimagines traditional superhero tropes to explore the struggles of power, identity, and survival within the realms of Black lives and everyday existence. It’s been a real privilege to read and discuss this collection with Gary Jackson.

McCall: What personal or lived experiences inspired you to write small lives? Were there moments, books, comics, or events that planted seeds for this particular universe?

Jackson: Oh, so many. The notes section in small lives covers some of those influences from comic books, music, and other phenomena—both lived and learned. And some of the characters in the book I’ve carried with me since childhood, playing pretend with childhood friends. Others were thought experiments that developed into multiple poems. But one of the larger imperatives for the book was a reframing of the paradigm that superheroes are, by default, white and male. Most folks, including myself when I was regularly reading comics as a kid, imagine some version of a Superman/Clark Kent figure when asked to close their eyes and immediately conjure the idea of a superhero. I’d like to disrupt that archetype.

McCall: How did your earlier books, Missing You, Metropolis and origin story, prepare you for writing this one? Did you have to unlearn anything?

Jackson: By the time I started writing the poems in small lives, I was already comfortable writing persona poems and had a good idea of how superhumans view the world—which is largely thanks to writing my previous two collections. I’m not sure I had to unlearn anything, but I did embrace the prose poem more fully for this collection. It’s a form that appears in previous books, but not to the degree that it exists in small lives. It helped me straddle the line between verse and prose, which is how I arrived at the idea of writing a “graphic novel in verse.”

McCall: What drew you to that hybrid form, and how did it shape the way you told this story compared to a more traditional poetry collection?

Jackson: I shouldn’t call myself a “failed comic writer” since I didn’t really try that hard to become one, but it was (and still is) a genre I desperately wanted to publish in when I was younger. Once I started writing in the core trio of voices that shape small lives, I knew I had stumbled into a larger narrative, so it took a while to figure out if these were going to stay as poems or grow into short stories (I do have a few short story drafts of a handful of poems that won’t see print, but I suppose never say never). I settled on the idea of a verse novel, but really it reminded me of a graphic novel—telling a complete and relatively self-contained superhero story. And I’d like to think of the prose poem as serving as the equivalent of panels in a comic, with the reader needing to fill in the action in the gutter/white space (page turn, even) between each panel.

McCall: Your collection is organized into parts, featuring a “dramatis personae” of the superhuman characters (The Invincible Woman, The Telepath, Willpower Man, etc.) that appear in the work. What inspired you to format your collection this way? How did you map out the narratives of your characters’ growth, decline, or transformation?

Jackson: In my last two books, I’ve gotten editorial notes asking for clarification on some aspect of my manuscripts. In origin story, it revolved around the erasure interviews that run through the collection. In small lives, it revolved around the personas and wondering if the collection needed a cast-of-characters-page to help the reader. I’ve since decided to embrace those editorial notes and use them as a fun prompt to include in the book—in small lives, I wrote that small poetic dramatis personae you’re referring to.

I immediately knew when writing the various personae in small lives that the three main speakers would be The Invincible Woman, The Telepath, and The Willpower Man, and so those were the characters I decided to hang the narrative arc upon. It’s too much to try to explain in a single question—but I had to wrestle with the plot for some time as I was writing the poems for this collection. Thankfully, after I had drafted my first “complete” manuscript, there weren’t many poems I felt I had to add to fill in narrative gaps. In fact, there were far more poems that I ended up cutting entirely. A dear friend gave me the perfect advice: don’t underestimate the power of implication, which was especially helpful in plotting and sequencing a book-length narrative of poems and resisting the urge to explain/contextualize every single action.

McCall: Superheroes are often seen as mythical figures that are larger-than-life, but in small lives, they also seem quite vulnerable. So, how did you go about balancing that tension?

Jackson: I had a lot of practice writing the poems in my first book, Missing You, Metropolis. The superhero personas in that book are firmly established Marvel and DC superheroes, but I was never that interested in simply recapitulating their heroic exploits. If anything, I wanted to humanize these figures, make their trouble real, which is something I intuitively feel when I read a well-written comic. I’ve always argued that comics are capable of being “high art” and should be able to shake off the stigma of being considered juvenile. Admittedly, that argument isn’t as difficult to make in 2025 as it was even 15 or 20 years ago (or maybe it still is, thanks to living in a world that’s now dominated by Disney).

McCall: How did you decide what form each poem should take, and what did those choices allow you to do with these superhero characters that strict verse might not have?

Jackson: I mentioned this earlier, but I’ve always enjoyed the prose poem as a form. It can organically rupture the reading experience: a reader can fool themselves into believing they’re reading a story, a narrative, and suddenly they’re in the middle of a lyric— a non-lineated poem doing all the poem-y things a poem can do. That tension between the form and content also lends itself well to exploring the psyches of characters that constantly feel unease in the roles they are supposed to fulfill.

Of course, a prose poem can also be perfectly at home as flash fiction, a brief vignette or scene, and it’s totally fine! In many ways, working with prose poems opened so many avenues of permission.

McCall: How did you use traditional superhero tropes like origin stories and superpowers to help you explore issues around Blackness and otherness?

Jackson: My favorite superhero stories were always in The Uncanny X-Men. Even as a kid, I recognized that mutants were allegorical for any discriminated minority, and so the superheroes in the X-Men were othered for the very fact that they had superpowers. The absurdity is, of course, that they are the only heroes who are othered for their gifts—no one commits hate crimes against The Fantastic Four or The Avengers (unless they accept mutants into their roster), but for The X-Men, that’s just another Tuesday.

But due to the stubbornly apolitical editorial mandates that steered many 20th-century comic franchises, that allegory for mutants as a persecuted minority could only go so far. Most of the X-Men present as white in their civilian identities. But what if they couldn’t? As superhero stories began to more aggressively mirror our current reality, it seemed like a natural fit to (re)visit that allegorical use of the superhuman as the racialized other with the characters in small lives.

McCall: When readers finish reading small lives, what do you want them to take with them—emotionally, intellectually, socially?

Jackson: I generally avoid prescribing what I want from a reader, mainly because I don’t want folks to feel as if there’s a right way to read these poems (though from teaching years of poetry, I also know there are plenty of bad takes and (sometimes intentional) misreadings), but I do hope the book conveys some sense of humanity in these speakers, complicates some of the superhero tropes we’ve all grown used to over the years, and presents the reader with a world where the default isn’t always white. Maybe a poetry reader will pick up a comic if they haven’t in a while. Maybe a comic reader will pick up a poetry collection. I’d be grateful for either. Hell, even both.

Gary Jackson is the author of the poetry collections small lives, origin story, and Missing You, Metropolis, and co-editor of The Future of Black: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry. He is the Toi Derricotte Endowed Chair of English at the University of Pittsburgh, and the Director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics.