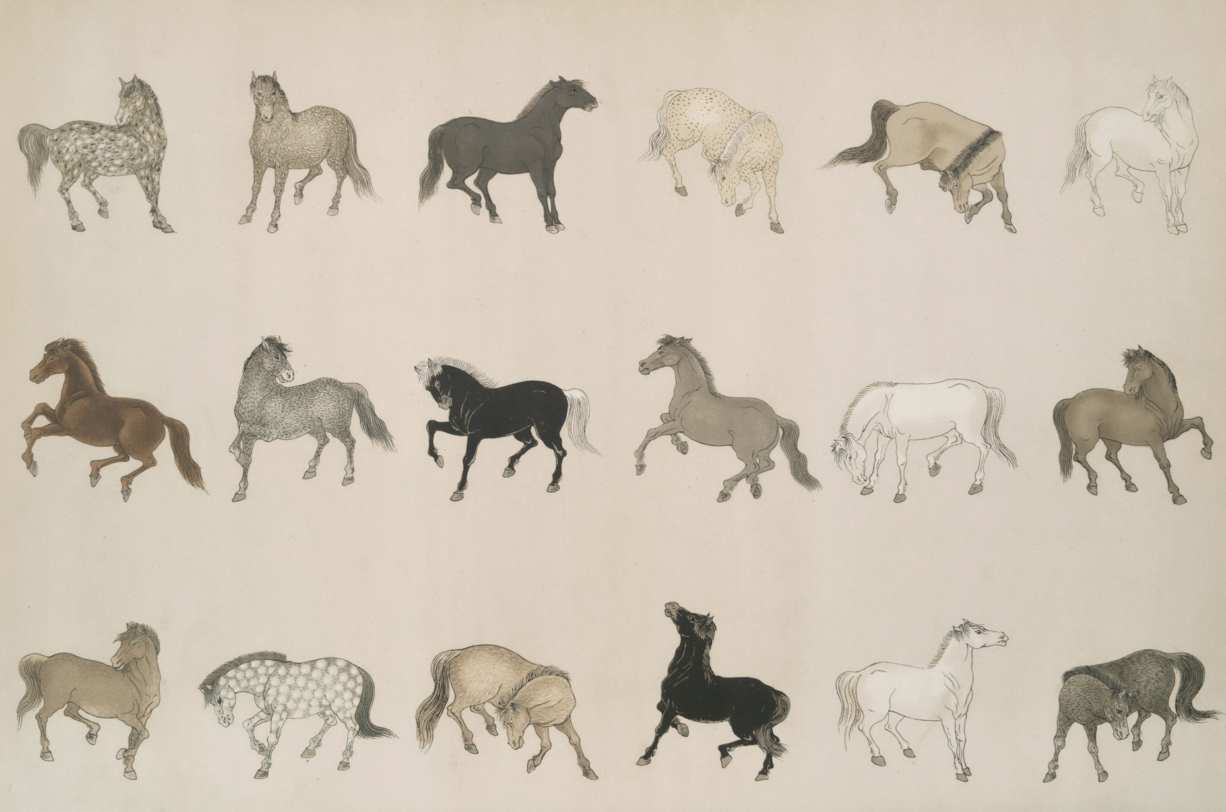

A Study of Horses

Matthew Wimberley | Poetry

Once, I turned catching the light of a late afternoon

through the maples—coin tossed to the dying

grasses and late summer clay and nothing else.

A little ways up the road, the Seventh Day Adventists

sold oranges and because I didn’t have any money

I pulled over to watch a horse I’d passed

by for years—always wanting to do just that

and always in too big a hurry to see the flies

which swarmed through the heat, mated, or died or

whorled around her face, and also how the dark hood

over her eyes looked uncomfortable, slightly crooked

not really lined up so she might see—the holes like holes

cut in a homemade costume a single mother

once made her child for Halloween out of an old sweater

—hose rolled into a headband to make ears

and a symbol drawn on paper and taped to the chest,

a garbage bag for a cape—the knot at the neck coming loose.

I don’t know why I’m thinking of it now

only how at this distance she stood so still. . .

how in her posture were all the possibilities

you could be trampled by—the invisible scrawl

her tail drew in the air dispelling the flies,

and the open sores making

a constellation of half-visible wounds

in the fur. For the rest of my life

this won’t change, no matter how hard

I squint into the bright day.

This dust, trampled earth, a horse whose eyes

seemed to glow behind their crude screen

like the phloem of black locust beneath

the bark—chatoyant, impossible to recreate.

I knew a girl in high school

who had to learn to speak again

after getting thrown from the back of a pick-up

after a football game one weekend. I heard she got better,

and works in a bar in Atlanta now

where they wear almost nothing and where

each night she makes mixed drinks—margaritas

and Johnny Apple Mules, and doesn’t get home

until the sun rises. She studied poems in school,

like me, and hasn’t been touched in years and so

maybe has figured out, if I had to guess, a way

to remain pure and indelible. In those days

the girl’s father raised Percherons

and sold them to farms to work

on hillsides covered in milkweed growing right up

to the crooked fences which had been there

for generations. And the horses were giants,

having descended, it seemed,

from the Holy Bible and the mouth

of God, how they commanded your attention

as they lumbered out of the morning, or dipped their heads

to drink from a vein of creek water, how they stood

upright on the crest of a hill at dusk.

Breath by breath the days fell away

—the crosses erected to mourn the dead, wreathed

in flowers and placed along roadsides disappeared. Storms

brought down trees on billboards advertising

year-round ATV rentals and salvation. Work

was never scarce—the tourists coming in from Florida

and New York, escaping the heat each May

stayed a little longer year after year

and complained when no one was available to clean their gutters

to the clerks behind the counter at the general store.

Before the ordinances designed for the tourists’ satisfaction,

when I was maybe seven, in church, I’d taken communion

and the blood of Christ was semisweet in my mouth

and reminded me of the almost metallic scent

of warm pavement in a short rain on the narrow roads.

And I figured out much later

how appearance becomes action, gradually, by doing

nothing at all. Every now and then, someone would slip a few dollars

from the collection plate and no one got caught. Then,

I wanted to come to a place I could be forgiven, and

maybe it is here, though the light has broken through the maples at just

the right angle to blind me, to make me look away

for a moment. What was the scattering

of leaves in the wind and the whoosh of water

in the river behind me, the white noise in the ear

the aftermath of ringing, like the church bell signaling the hours?

Out past the beech forest, and west

the sun is beginning, at last, to disappear and this pasture

is going on to become a remnant. And maybe

across town a woman who has lived alone

for fifty years in the house she was born in

sits down and closes her eyes to picture the woods

before they were leveled for condos all around

her now—so that it looks out of another time.

As a child I saw this place as mostly empty and quiet

and watched my stepfather wake in the middle

of the night to respond to structure fire,

and then at last return for good as my father. Somewhere

through that rough darkness—the radio

still clicks with his voice here and there

in the bedroom where my mother would stand—I can see her

in a white nightgown and the moon over the ridge

through the window—in the absolute center

of silence, and she must be praying, mouth closed,

though she says nothing.

And me? I’ve been studying,

just like the dark has, how this horse cocks one ear

in my direction at all times. By now

night has fallen on her back, and she has begun

to carry it over the hill and up toward

the bales of hay which listened

and I could hear it too—alone

with my thoughts. It hummed a little in the background—

like Time, like a prison guard

with a tune stuck in his head, one I learned

as a boy—there in the passenger seat

looking across this same open field and the quiet

that afternoon which once could have been

the last day on earth—

just a slash on a concrete wall now, and the horse

in a crooked amble across the empty field.

Matthew Wimberley grew up in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The author of two collections of poetry, Daniel Boone’s Window (LSU, 2021) and All the Great Territories (SIU, 2020), Wimberley’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in 32 Poems, Image, Orion, Poem-a-Day, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. He lives and teaches in the mountains of his childhood.