Crazyhorse Reading Series: Julie Orringer

October 13, 2015 | Uncategorized

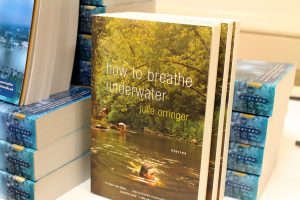

We’ve been waiting for just a few moments when the A/C kicks off. Over a hundred people have come to hear Julie Orringer, author of the short story collection, How to Breathe Underwater, and the novel, The Invisible Bridge. Anthony Varallo, fiction editor here at Crazyhorse, walks to the podium to introduce her. He’s been teaching her stories for years. For his writing students, Orringer’s work offers an opportunity to, “begin to see how it might be done. Not how to write a short story, but how to think about their experience as something worth writing about, how to see the story as an invitation to explore their life.” Suddenly, the heat seems less oppressive. We listen eagerly, and indeed, an “invitation to explore” is exactly what we find in Orringer’s short story, “Note to Sixth-Grade Self,” and her advice on craft.

The reading begins suddenly: “On Wednesdays, wear a skirt. A skirt is better for dancing.” Written in second-person, the story chronicles the advice that an older woman gives to her sixth-grade self. The advice is also the chief storytelling device; we construe a plot from assumptions we form about  situations that may have prompted the narrator’s advice. The narrative voice is not jarring, but welcoming: it invites us into the story. We’re not outsiders; we’re included.

situations that may have prompted the narrator’s advice. The narrative voice is not jarring, but welcoming: it invites us into the story. We’re not outsiders; we’re included.

As the reading ends, the audience—mostly young writing students—is eager for Orringer’s guidance on craft. Most questions concern decision-making, and Orringer advises to let the story do the decision-making. Using “Note to Sixth-Grade Self” as an example, Orringer explains that the choice to write in the second-person imperative was sudden, not painstakingly deliberate: “It all just happened at once.” In moments between waking and sleeping, she thought, “On Wednesdays, wear a skirt. Skirts are better for dancing.” And that was it.

Other questions concern plot. Did she plan plot beforehand, or “discover”  events and endings as she wrote? She affirms these questions; tackling them is, “Something I have to keep re-learning every time.” Even when the inspiration for a story revolves around a single event, the characters don’t let this event occur. “It’s hard to trust the change in the vision,” she says. But that’s okay. “A story that works,” she notes, “tends to subvert your own expectations. It tends to be smarter than you are.”

events and endings as she wrote? She affirms these questions; tackling them is, “Something I have to keep re-learning every time.” Even when the inspiration for a story revolves around a single event, the characters don’t let this event occur. “It’s hard to trust the change in the vision,” she says. But that’s okay. “A story that works,” she notes, “tends to subvert your own expectations. It tends to be smarter than you are.”

There’s a way to let the story subvert your expectations: let your unconscious do the work. “Hold it sort of softly in your mind without trying to solve the problems of it,” she says. “And, and the mind, that amazing organ, does what it does, it does its dance . . . and it will drop into the little gumball slot of your mind like this perfect answer. Not the solution to everything, but the one line, the one idea, that can get you back in, get you started.” One line, like “On Wednesdays, wear a skirt.”