An Interview with Imani Perry, author of Black in Blues

April 8, 2025 | blog

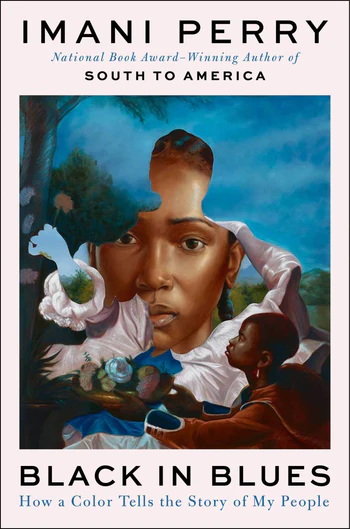

Celebrated author Imani Perry recently spoke at the Gaillard Center in Charleston, in association with the International African American Museum. She discussed her most recent book, Black in Blues, an exploration of the color blue and its presence and symbolism throughout Black history.

Lenore Barnes, MFA student at the College of Charleston, had the privilege to further discuss this book with Ms. Perry.

Barnes: I love the concept of “home house”—the dwelling where the family gathers. Black in Blues opens in your bedroom, in the home house. Was it instinctive or a more deliberate choice to begin this book in that space?

That house was my first home, and I felt like that room was my first room. So, I began surrounded by blue. I even recently learned that I had jaundice as a newborn and the treatment at the time (1972) was to place babies under a blue light. All of that to say, I guess the beginning chose me. Recently our home house burned down which was devastating. In fact, it was the night before my first book event. So it feels even more like that beginning wasn’t something I chose, but rather was called to. Because now the house is at home in the book.

What first prompted you to keep “blue notebooks”?

I usually jot down ideas if there’s a book or an article I’m thinking about. And that process took place over years with Black in Blues. I wanted to hold those ideas in a separate place from some of my others because I was writing in a new form. But then I also just kept finding these beautiful blue notebooks and it felt like kismet. Blue books for the blue book.

You wrote that “Blackness…organically reaches across borders. And I followed it.” You followed it from the South to West Africa, the Caribbean, Brazil, South Africa, Australia and elsewhere. This feels like a daunting task. How did you structure that research journey?

I love a research rabbit hole. And of course it helps that so much of what is in the book covers subject matter that I’ve been exploring for three to four decades. It is one of those books that really benefitted from my iconoclastic and voracious reading habit. There were all these moments in the process where it was necessary to collect and then prune. So I’d want to follow a thread, I would built a mini-archive on that subject, and then the task would be how to tell that story using a few examples, and how to allow those examples to fit into the larger arc of the book. As an associative writer it is extremely important for me to keep track of what I’m excluding and including and why. And the why is both a matter of illustrating a point and also craft- we need stories that are true and memorable and also leave space open for the reader to discover more elsewhere and or craft their own stories.

Reflecting on the varying emotions evoked by the sight of water, depending on one’s history, you wrote that in water you “see God and slave ships both.” How do you reconcile that—or don’t you?

I don’t reconcile it. I respect the water the way I respect a graveyard. There is a holiness and a humility there. I love to swim in the ocean. And when I am in that water, my tendency to be a scaredy cat is muted because I am so joyful about the majesty and vastness of the water. It makes me courageous. And that is what Black history does for me and part of what it does at best for anyone who reads it. We can learn so much about human capacity in the face of cruelty and violence, about imagination and grace which required and require enormous courage. The story of the water, the fact of the water, holds all of that and more. When Toni Morrison said water has perfect memory, it was a sermon in a sentence.

“Honesty requires a great deal of discomfort. But here’s the truth—we didn’t start out Black.” This is a fascinating observation about the role of the “conquering eyes” in labeling a collective identity and the actual diversity that exists among “the people we now call Black.” Did you experience unanticipated discomfort in researching and writing this book?

No, I chose the discomfort because I wanted to tell the story true. True stories require discomfort. But also, I saw it as an opportunity to model a maturity about faith and meaning and identity. I don’t need to believe that there is some essential meaning to race to say that Blackness means something to me. I think whether it is matters of religion or citizenship or anything else we hold fast to, we must explore the how and why we got there and whether it continues to make sense. One of the things that worries me is how often we remain unquestioning about that which we love. I think if we love something, deep examination is one of the greatest forms of care.

You used the term “quilt” in describing both South to America and Black in Blues, referencing the fact that there is no single story but a set of stories and experiences. Did writing South to America plant the seeds for this book?

The two books were sort of born together. I had the early titles for both written and placed on my spiritual altar for years. But certainly every book helps me refine my method as a writer, even though I explore different forms. But I’m always trying to learn through writing and its part of why, for me, the writing is in fact the best part. I know many writers like to have written more than they like writing. Many amazing writers feel that way. But for me the thrill is in the process of discovery most of all. And even now, when I’m in conversation with people about the book, I’m learning from how people respond and the stories and insights they offer. That learning from readers becomes part of my instruction as a writer. I learned so much from the responses, both positive and negative, to South to America.

You reference photographer Dawoud Bey’s statement that “art is the thing we bring into our lives to transform it.” How has the fruition of Black in Blues been transformative for you?

I’ve been overwhelmed by how many people have said that the book has been helpful to them- writers, artists, intellectuals, as well as folks just trying to make sense of this moment. I am so grateful that it is being received as a work of art that has a use in people’s lives. And so I’ve been able to think even more deeply about this relationship between art and community, from the perspective of being an artist. As a scholar and an intellectual I’ve done a lot of explanation of that process, but I love that I’m now DOING even more than explaining.

You’ve described yourself as an “associative writer”. Could you expand on that?

My professor in college, Robert Farris Thompson, talked about Hoodoo as an associative belief system and I re-encountered that while writing Black in Blues and it was an “aha!” moment for me. Coming from this tradition of jazz, improvisation and making do means that I have an aesthetic and cultural sensibility that leans towards collecting many sources of information and figuring out how to put them together in order to create something that offers insight. And doing so is not just a means to an end. The crafting of the relation, the composition, has meaning. I refuse to be bound to conventions of storytelling. I will use them when useful, but I’ll also stitch and re-stitch when I need to get to a truth that the conventions don’t lend themselves to. So to be more concrete, in the book I don’t speak of “myths” when I talk about folktales. I treat them as truth to the extent that they revealed a moral universe and a means of interpretation. That’s not what academics conventionally due. We tend to make a clear distinction between legitimated “fact” and the things which are assumed to be imaginary. But when we do that, we miss so much of human thought, experience and interpretation. So now when I read a spell I’m not interested in saying “that was fiction”, I just want to understand it in the context in which it was being used. And put that into my stories of the past.

You wrote that “Conjurers survive conquerors” and urge the reader, and yourself, to “haunt the past to change the present and claim the future.” Would you comment on the connection between these ideas and the art on the cover of the book?

I love Titus Kaphar’s paintings in general and in this one “Seeing Through Time” the cut out of a historic painting becomes a portal to the past for a contemporary woman. I identify with that woman. I’m making space for myself in the past and I’m walking around and paying attention as an ethical practice. If the records of the past leave my ancestors unnamed, then I find them by other means. And I learn from them how we are replicating the violences of the past, the very ones we pretend to have rejected. Because we can’t get closer to being in right relation to each other, the earth, and the ones to come, if we aren’t honest about what we are doing today.