Grajaú

Gabi Ragazzi | Essays

Grajaú is a place that molds around the edges. Beneath the cracks in the wallpaper that no one ever bothers to fix, the walls turn black then ooze and the dirt gets kicked up from under the floorboards no matter how many times they are polished to a shine. Up on their wooden perches, the saints turn gray, then black along their creases. Some of them smile. My grandfather put them up, I think, to be warm and welcoming. By the time I’m old enough to remember them, they are always sinister.

Their couch always smells of something. I wish I could tell you the something; I wasn’t able to identify it at the time, so I think it must’ve been medicine, or nicotine. Something greasy and cold got trapped in that couch, got smeared across the plasticine cover that was placed way too late to save the threads already several stops past frayed. Maybe that frigid thing was Ricardo, without whom the couch would barely be identifiable.

My uncle is a cruel reflection of his father. Wide and solid, with the kind of rigid potbelly that seems a texture humans shouldn’t be capable of. They have the same nose, scruff, but Ricardo is taller, more imposing. He kept his hair deep into his sixties, and when he talks his voice doesn’t have the same wheezing and scratching that his father’s does, even though he’s smoked a pack a day as long as I’ve known him. Always, always, he is damp. Clammy and trembling and wet, even his voice seems to thicken the air with impermanently gaseous spit.

First, I hate him. One day, my mother explains to me that her brother is sick, that the way he is is not his fault and somehow I hate him more.

Ricardo is always kind to me. My mother says he is a terror, that his temper once split the family in two. My father ripostes him, dodges him with confident niceties and the easy, practiced smiles he reserved only for those outside the family, always finds a reason not to be in that house for longer than a moment. Everyone treats my uncle like this wild, terrifying thing, and I let it justify my distaste even though he only smiles at me, wraps me in hugs that smell of unfiltered cigarettes, and asks me questions about my life.

When I am twelve, he attempts to get neurosurgery from a guru. He has managed to squirrel away his antipsychotics long enough to find another way to self-destruct, but once again he is thwarted. My mother finds out and stops him.

At times, I wonder if the only thing standing in the way of his annihilation is the careful ministrations of his desperate family.

He is loved so deeply – the blood of their bond has soaked the ground of this place so deep that their pain and hatred has not yet reached the bottom of it. My mother cries on the phone when he calls, but she never fails to pick up.

In a moment of weakness, I tell my mother that he upsets me because I understand him. He is sick, and so am I, and though I knew that it was not in the same way, it scares me to see him fall apart.

This is a lie. That is not why I hate him.

It’s a beautiful thing, a family working together.

It’s a terrible thing, a family helpless to stop him from setting himself alight.

Ipanema

My mother’s house is pristine but it is not really hers. You must belong somewhere quite a while to let the cobwebs build up in the corners you do not care about, to let the world invade in through the edges until all that’s left fits the shape of your life more exactly than you ever could have made it. She has not the patience to do this, so instead she drapes herself over that house, suffuses it with her paranoia and perfection, fills its every mood and moment with herself.

This year, it trembles.

The tablecloth is starched rigid and tough. It holds onto the crumbs of her cafézinho only so long as it takes for her to step away. A moment later and her sister has swept it to the laundry once more. Recipes in the kitchen are held together in their books by the barest remainder of faded spine and the tension of their neighbors tightly packed against them. If she were to draw them out for use, they would scatter, but she has not cooked in months.

This year, she has no interest in looking back. So, she holds on tight, commands the house to still and warp in her image, maintains it within an inch, so that she can recall every bit without looking. That’s the only way she gets to keep anything. Even now, when her voice no longer rises above a whisper, when her sentences end in a whimper and her eyes pan blankly over her work with no recognition, the house moves on without her anyway. Such is her control. Such is her need.

My brother and I have been called away from our lives to be load-bearing in hers. Everyone tells us it’s because they miss us, because it’s been years since last we’ve been home. They are liars and bad ones, but we let ourselves be conned. On our flight in, me and my brother talk about leaving our family behind. As we land, I silently hope that we are liars too.

There is a place in the living room she hasn’t gorged upon. His force of personality has kept it his, even though he ceded it to her. My father’s computer is there, sitting idle where she cannot pilot it. His television, too fancy for her rustic tastes. The dog he gave her, still listening for him with every rattle at the door.

There is a place inside her she hasn’t reclaimed yet, either. The many fragments of her she gave so freely that he did not even notice her shrinking. In his leaving, he has taken those too. Everyone worries that there is not enough of her left.

“She’s entirely resistant to treatment.” My father’s voice does not waver over the phone, “Her psychiatrist says that she’s not responding to anything as expected.”

In the time after their divorce, my father is in charge of her psychiatric care. This is only natural. I do not dare say this aloud. I do not feel the fear and sickly rage where they sit inside my chest. This is a time where such things make sense.

“What is she taking?” My brother, always the scientist.

In the list of medications that follow, I note with distant curiosity how familiar the set of names. Distant by choice. I am a thousand miles deep behind my clenched teeth, settled somewhere in my gut where only the echoes of their voices make an impression.

“Mm.” Felipe is cracking a case wide open. He must treat her like a patient. He cannot, after all, treat her like his mother. “Well, she hasn’t tried everything. A year seems like a long time, but that doesn’t mean it’s not working.”

“She isn’t getting better.” My father’s guilt makes him foolish. He’s ready to do anything.

“What’s the alternative?”

“The psychiatrist said we could try electroshock therapy.”

Oh. That simple. Just electroshock therapy. Why didn’t we think of that earlier?

I snarl and bite. I weep and wince. I strangle them, tell them they are betrayers. I beg them, whine at their feet to reconsider. I do none of these things. I am so deep in my body that I hardly move.

They mean well. They love her, in their way. But they are not her. My mother has gone mad and the world is fixing her against her will. My mother has gone mad and everyone is pitching in. My mother has gone mad and they are going to burn her, fry her brain, sear out that terrible grief and put her right. When they’re done, well, maybe she’ll be smaller still but she won’t be mad and then she will be okay. Then we will be okay.

Leblon

The apartment in Leblon is a terminus to a long line of empty places. It’s quite beautiful, in a modern interior design sort of way, all tall elegant squares of white and black and grey. One wall is floor to ceiling windows out into Rio’s chicest neighborhood, another a long polished mirror that perfectly accents the glint of the sharp, unobtrusive mid-century chandelier. I remember thinking it looked massive when it was empty. It somehow looked larger with all of our stuff in it.

Our furniture doesn’t quite match, but we do our best. There’s the shock of faded red and green in the carpet we’ve held onto since Colombia, and a deep chocolate brown in the dresser that’s older than I am, a gnash of intricate criss-crossing patterns carved into wood. My book collection looks even older against the sharp cleanliness of the built-in desk for my room, soft and wilting edges fanning out against unforgiving white-plastic shelf. It’s the sort of incongruity that might bother in a place you live in for a long time.

I don’t pay it much attention, to be honest. My room works well enough as a space to put my computer. My mother picks out an inoffensive cream for the bedsheets, and I sleep in them after staying up into the wee hours, studying. I leave the walls bare. I stuff my school papers into a drawer. Besides my books and my clothes, I don’t carry anything from the last place. I take pride in that, how little space my life takes up. The perfect twenty-first century nomad.

I turn seventeen in that house, and I dream of having a good reason to suffer.

Life is easy. I go to school, come home, play games, study. On most weekends, my father insists we head to a nearby beach town to relax. Sometimes I even succeed in convincing him to leave me behind at home so I can see my friends. I don’t see them. Mostly I stay in my room. Study. Play the same game over and over just to give my hands something to do.

I do not want for anything. I have not been taught to want. I am a writer even then, and I know that empty lives do not make for interesting stories. My body seems to know this intuitively, and so I hurt easily, cry liberally. I convince myself that this means if I am simply receptive to it, ready to feel, then my great story will come. So, I wait at home. Study. Play games. Do nothing at all, or lots of things very much like nothing.

But we do not get to choose how we suffer. When finally I break in that cinematic way, tear and scream and weep and look for the exit, it is not a good story.

I become unable to study at my desk. My body refuses. Bones and muscle alike freeze and twitch in place when I sit there, so my notes are that day scattered at the dinner table. There is a math exam in two days. My lungs cannot seem to inflate. My family is leaving for a trip. The house is empty and dark, and I am alone because I am usually alone. I have been trembling for six hundred days and do not know how to count any higher. There appears to be some sort of boiling liquid under my skin, and its crackling has gotten so loud that I cannot hear my heart beat. My reasons are pathetic. They are enough.

As my mother leaves for the car, my knotted brain comes loose. I call her to tell that I am going to kill myself, but I cannot use those words because I am absurd and she has lost her brother, is losing her marriage. I am losing a grade. She does not realize my meaning and vacations anyway.

*

By the time I am eighteen, Grajaú feels at risk of collapse.

For more than half a century, that house has sat, saturating day by day with the mores of the family. My grandfather, while he was still a young man, promised each of his children a piece of it – Leninha, the eldest, snatches what used to be the bedrooms, Luizinho, the backyard. Zé is a memory on my grandfather’s wall. By the time my aunt Regina, the fourth child, comes old enough to claim her father’s gift, she and her husband must build a second floor in order to find space. Ricardo sleeps in the room by his father. Never bothers to put up a barrier. Never pretends he has a life all his own.

Lucia nearly escapes, goes nearly far enough to have her own life, to a street twenty minutes away. My mother spends her entire life knowing she will need to take care of them. Even as the youngest, she is the most sensible, the most capable of putting her anxieties aside and finding what her siblings need. When her mother falls sick, it becomes obvious that she has inherited the tendency for caretaking from her father.

Then her life changes. She meets my father. She puts a distance so great between herself and that house that me and my brother do not recognize our cousins until we are five and ten.

Thirty years on from her escape, there is a gravitational pull to that house. Even I can feel it. Once, it kept the whole family from scattering to the winds. Now, it squeezes them close, so close they bruise. The bricks have held onto the fallout of each disagreement, and their habits, good and bad alike, stow away in every cupboard and closet. The entire place is heavy with their lives, and rich with their hurts.

Sometimes, when I visit, I wonder if I might’ve been happier there. It is not a happy place, but there is a fullness to it, an obvious clarity to its miseries. Maybe when my mother broke away from what seemed like her destined fate, when she chose to leave home instead of stay, we were all left adrift because of it.

Other times I think that perhaps Grajaú came with her and she never did really outrun it. That instead she brought it along in the fibers of her flesh, every day getting thicker and heavier and harder to carry. That when I was born, I inherited it too.

A half hour after my breakdown back in the Leblon apartment, my mother seems to have become overcome with a kind of intuitive, parental fear. She interrupts my attempt to shatter my finger bones against the doorsill of my room, orders me a cab that is more expensive than we should be wasting our money on to bring me to join the rest of the family, whether I would like to or not.

In the year that passes after, that heated, burning sap caught between the sheets of my skin boils off and leaves in its place something dull and leaden. Across the age of eighteen I learn that wanting to live is not the default setting, and everything that follows is in a new color. I do not tell this to anyone. Who could I tell? The shame of the absurdity in my overreaction sticks closer to myself than any desperate wanting for help.

You might imagine that there must’ve been something else going on. I have often wondered the same. Some greater, darker truth might make this all less an overreaction, might bring balance to the actions and the reasons. We cannot all simply be weak-willed histrionics, can we? I have lost many days to this exact wondering, but I unfortunately have not come here to report some satisfying answer. Since you have read this far, though, let me offer my best guess.

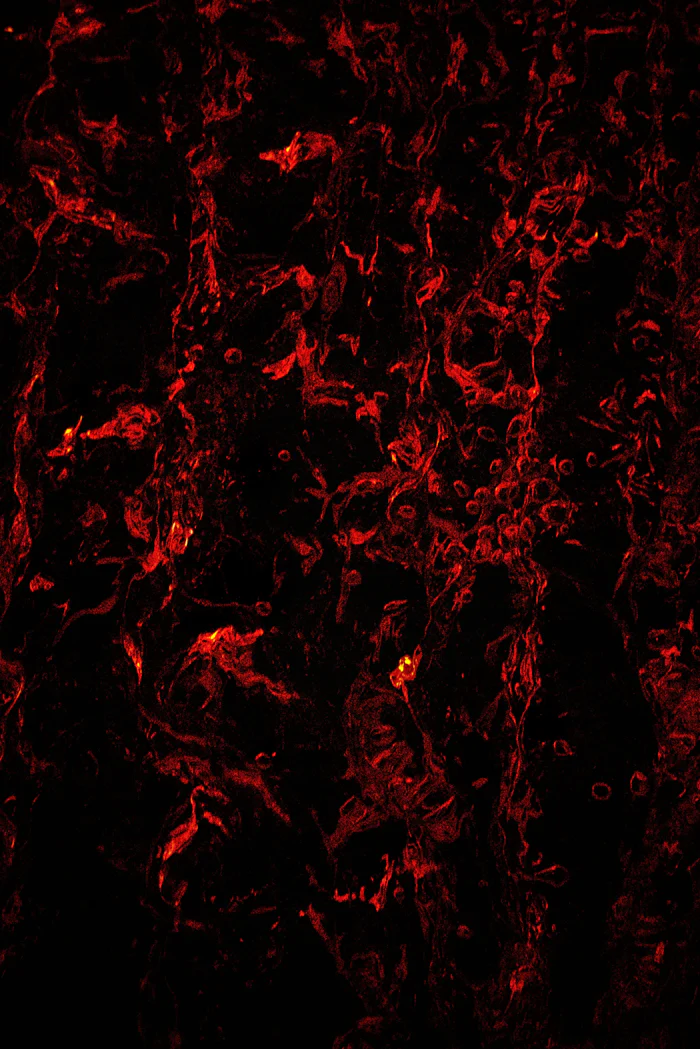

Some people are born to burn. Some of us are dipped in gasoline at the womb, soaked through to our marrow with panic and pain before we’ve even met the world. It sloshes around inside us and calcifies with our bones and we carry it with us even when we don’t want to, and then it does not take a blaze to set us alight, only a spark.

My uncle burns because his brother died. Because they fought each other as brothers do, because a house that size should never have fit seven, because a life that size could never fit the both of them and even so because they were just not of a kind. And their rages would have chased them across the ages and they should have grown to drive each other mad but instead his brother died. And now he burns.

My mother burns because my father left. Because she gave him everything of her, sacrificed her selfhood at the altar of our family, of his career, and in trade she got a piece of him that he took with his leaving. She was promising, and brilliant, and her family needed her but so did he. And now she burns.

Their good reasons have given way to my bad ones. Their grand struggles have fed my minor ones. The fat off of their searing bodies has liquified, mixed into their blood and nestled into our genes. My body remembers harder lives than mine, and now all that grief has nowhere left to go.

When I am eighteen I burn because I am flammable. Sometimes that is reason enough.

Gabi Ragazzi is a young writer from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, though they grew up all over the world. These days you can find them writing at a coffee shop in São Paulo where the coffee is acceptable at best and the cake excellent. This is their first publication, but you may see more of their work at gabiragazzi.substack.com.